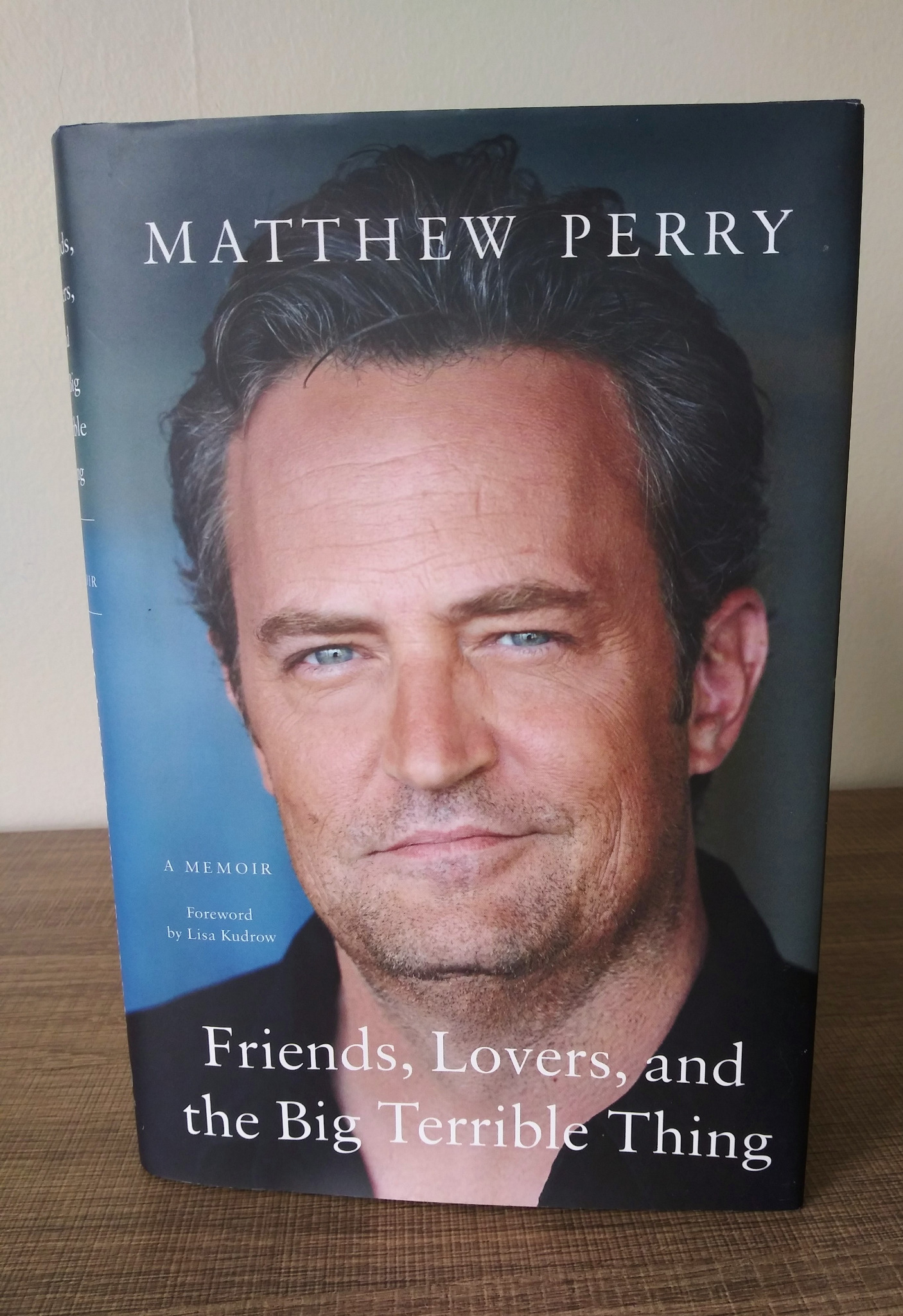

Book Review: Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry

Content warning: This book contains descriptions that others may be sensitive to, including vivid depictions of medical conditions and discussions on drug and alcohol abuse and withdrawal.

My husband says I need to stop talking about Matthew Perry.

Apparently I’ve accidentally stumbled into long rants on several occasions, bringing him down with visceral hospital scenes and discussions on addiction and depression that end up sounding whiny and sad with a strong dose of cringe. If you decide to read this book, you are accepting the responsibility of reading about all that; you are respecting the author's truth. Perry’s Chandler-esque self-deprecating humor does nothing to make the topic funny, but rather makes it even sadder, making it a truly heartbreaking read. If my husband ever had any interest in reading this book (he didn’t) I killed it. And now I have to write about it.

“Hi, my name is Matthew, although you may know me by another name. My friends call me Matty. And I should be dead.”

Oh shit, the prologue just jumps right into it. Suddenly we are seeing Matthew/Matty at what we assume–and eventually hope–is a turning point for him, in the worst pain of his life while a friend and a nurse at the sober living house he’s living in are debating whether he needs to go to the hospital or he’s just trying to get drugs. He grants us immediate access into his thoughts, his fears, and how addiction has ruled over his life–showing a raw vulnerability I feel like I haven’t earned. It’s a pretty intense way to start the book and sets a tone and pace that doesn’t soften and slow until much later in the book.

Thankfully, he releases us from this turbulent beginning to talk about his childhood. I am ashamed to admit that my initial reaction was… “That’s it?” (Clearly a sign of how desensitized I am from reading the news daily.) I already know, through other reading I’ve done, that trauma is not about what a person experiences but how it affects them over time. While many people out there experience “capital T” Trauma in their childhoods (i.e. physical or sexual abuse, etc.), there are a million different reasons people may carry trauma from infancy or childhood whether they recognize it or not. After over 30 years of therapy, Matthew Perry knows and understands his trauma, and with every family anecdote he shares throughout the book comes a snarky or regressive comment that illustrates the pain he clearly still feels from it.

He refers to one particular story many times in the book in which he traveled from Canada as an unaccompanied minor at age five to visit his dad in California, an anecdote symbolic of his loneliness and feeling of being “unparented” that has stuck with him throughout his 53 years of life. Like many comedian actors (and like his character Chandler, who is difficult to separate from Matthew based on how similar they are and how much of himself he put into the role), he leaned into comedy as a way to obscure his feelings and gain attention, particularly from his mother. But what I found to be the most compelling likely source of his addiction, at least chemically, is his relationship with drugs beginning within the first two months of his life. Back in the 70s, it was not uncommon for doctors to prescribe barbiturates to colicky babies, and Perry claims there are photographs of him passed out, high on drugs, as a tiny infant.

The beautiful thing about this book is that it is not read as much as it is experienced, and through that experience comes profound change, wisdom, and sympathy.

My response went from the initial sarcastic “oh boo hoo you’re a rich movie star with the same problems as normal people” to the disgusted and appalled “dear god what are you doing to yourself?” and, finally, to the near-tearful “I just want to hug this man and tell him he’s okay” (cue Jackie DeShannon’s “What the World Needs Now is Love” in the background).

Many people have said it, but it bears repeating: Matthew Perry is incredibly brave for putting this out there. He is unflinchingly honest. He says some pretty hateable things about other celebrities, people, himself… He is as bitter and blunt as the grumpy old man at your local bar and as tender and sensitive as a newborn baby. Unfortunately, it doesn't feel like he wrote this in a healed state of recovery, rather during one of his many brief periods of sobriety--and as the book starts winding down things get a little murky. There are back to back contradicting statements and vagaries around his current drug and alcohol use. He somehow aims to project a sense of hope to other addicts while still illustrating his clear inability to "get the monkey off" his back, as he puts it. This is perhaps the most honest aspect of this memoir of all–that despite his admirable turn toward advocacy and his many references to how lucky he has been and how grateful he is to the many people he credits with saving his life (he particularly shows a strong sense of gratitude for Friends, rightly so), there is no way to neatly tie this story up with a bow.

Anyone who believes that addiction is not an illness will hopefully find Matthew Perry’s memoir eye-opening and illuminating. Those who have wrestled with demons themselves will hopefully find solidarity.

0 Comments Add a Comment?